Representing Hierarchies

published on Jan 01 2026

Very often we have to deal with hierarchies of things. HTML elements, files and folders, scene graphs... basically, anything where a node might have an arbitrary number of "child" nodes, which can also have their own children, and so on. There are a couple of general ways to represent this type of structure.

The Obvious Way

One obvious way is storing an array of pointers to child nodes within a node:

struct node {

std::vector<node*> children;

};

An actual implementation might have more details, might actually own the child nodes, or not use `std::vector`, but you get the idea.

This approach is actually pretty nice if the algorithms you'll be running on this structure ever need to access a child with a particular index (e.g. the third child of the root's first child).

The downside here is that the `children` array needs to be backed by dynamically allocated memory. So now we have more allocations. We also are going to have to worry about _how_ these allocations are made (unless we are okay with always using the same allocator for all of them). There are also more opportunities for cache misses due to extra pointer dereferencing.

One could try to improve this by using a fixed-size array (if you have a small upper bound on the potential number of children), or implementing small buffer optimization (i.e. small string optimization, but for buffers).

If you don't actually care about accessing children by index though, all of this sounds like a drag.

The Allocation-Free Way

There's a pretty obvious alternative representation:

struct node {

node* first_child;

node* next_sibling;

};

A node contains a pointer to its own first child, and a pointer to the next child of its parent (i.e. its sibling). This completely obviates all the memory management problems and eliminates extra indirection. It's also very convenient to use with intrusive data structures.

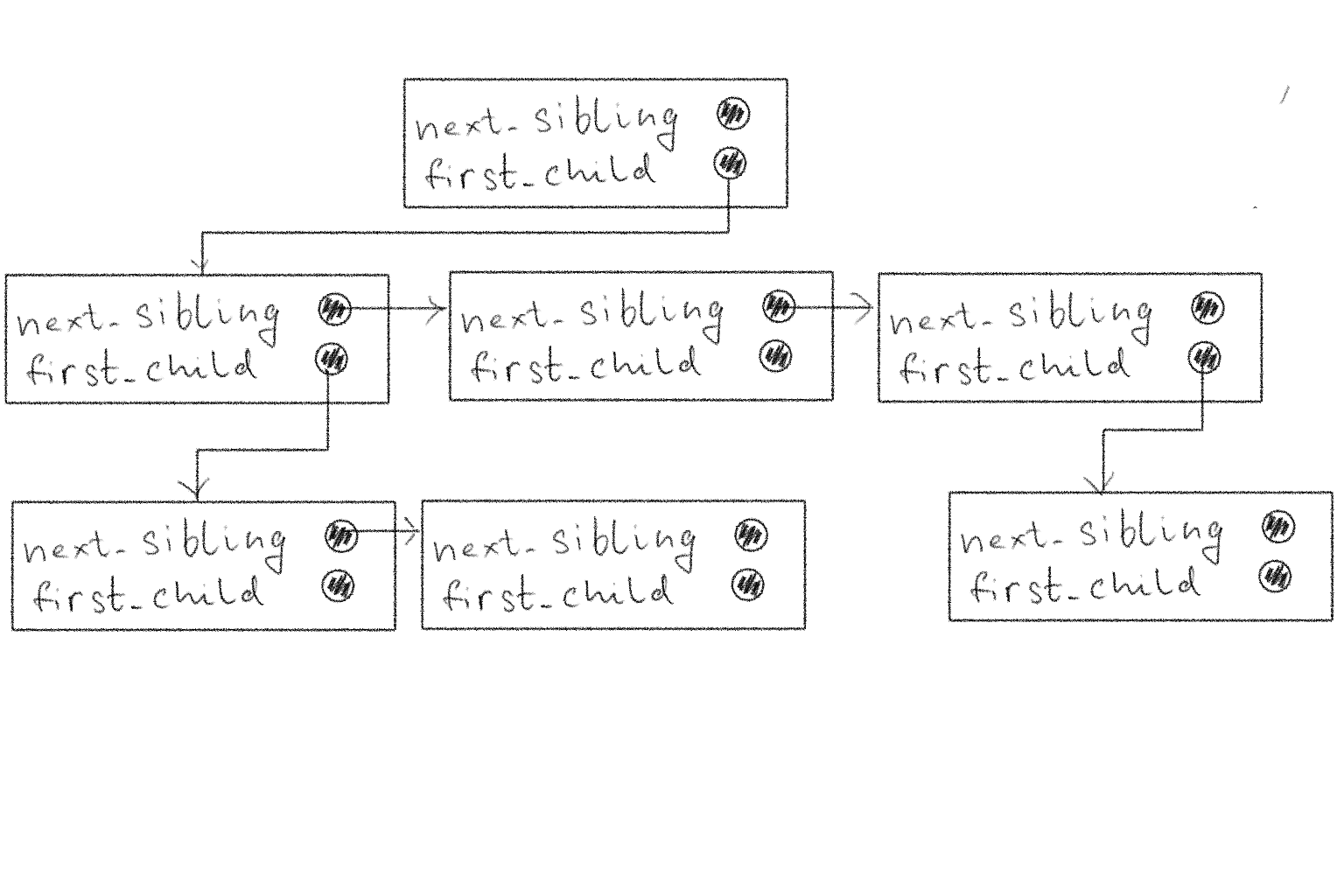

Here's an example of what an instance of this structure could look like. Here, the root has three children, the first child of the root has two, and the third child of the root has one. All the other nodes have no children.

The downside is - accessing a child with a particular index is no longer "free" since you have to linearly follow the sibling pointers starting at the first child.

I had found this representation useful in the past (for example, when dealing with 3D transform hierarchies) because in many cases, my code was just spending time traversing parts of the tree, not caring about any specific child of a given node in particular.

Like this post? Follow me on bluesky for more!